Since its announcement in spring of 2011, I’ve been excited to experience Papo & Yo. Just from the initial teaser trailer it seemed like something whimsical and unique. It wasn’t until closer to its release that I became aware of the dark life experience that fueled its inception. The trauma of Vander Caballero, the project’s creative director, seemed inspire a new idea in the sea of game sequels drowning the industry. How can one take their childhood trial of their alcoholic father and gamify the experience? I downloaded the title with hopes of deconstructing the creative process. Hopefully, I would be able to take away one bit of inspiration or insight I could apply to my own creative methods.

The game is easy to look at. It doesn’t take place in the future with ray guns and plasma rifles nor does it take place in the forest where dark elves and kobolds roam. It seems to take place in present day, but a mystical alternate interpretation of favelas, South American shanty towns. Chalk drawings of gears, handles, windup keys, and ropes provide the central interactions around the world, each peeling away the realistic facade to reveal the blank paper like world beneath. The composition of the real and the whimsical solidifies the feeling of seeing the world through a child’s vantage point.

The music only served to solidify the playful nature of the game, while flavoring the world with additional South American flavor. Executed well, the beats did not overpower the experience but only served to accent the mood presented by the game.

Monster had a unique look to him that seemed to border on cuddly and dangerous. I can assume this is intentional seeing how Monster’s look has transformed from the initial teaser video to the final product. This much was inferred by Caballero in an interview. It was interesting to feel the caretaker relationship between both Quico and Monster. They seemed to need each other although it was obvious the brunt of the tension is grounded in the nature of Monster.

Some of the level design was particularly memorable. Stacking houses one by one until they towered in sky was extremely empowering. There was much glee in my heart twisting and tilting the tower to reach previously unattainable areas.

With so much that I liked, there were elements that kept me from truly feeling engaged by game. You start off the game with very little context. While this may have been intentional, I found it disorienting and off-putting. There was no initial purpose to any of my actions other than puzzle solving busy work. The main story thread seemed widely spread out through the game. If it were condensed I would have felt a bit more connected to the overall purpose and objectives of the characters.

The navigation of Quico, the main character, seemed too responsive which made him hard to control or snappy in movement. In contrast, Quico’s jump action had a slight delay. The animators probably wanted a bit of anticipation in the jump, but it just made the character feel sluggish when jumping. This is a no-no in platform games.

Later in the game there were some puzzles that utilized the design rule of 3. Pull this lever to drop a box. Now, do that twice more but with more complicated jumps, and avoiding a raging Monster. In certain cases this felt forced and served to drag out the experience even more.

As a designer, I believe if one is to tell such an emotional tale with such a short arc, the game should shoot for the length of a movie. An hour and a half should be sufficient enough to get people on the hook, but not feel as if the experience is dragged out. While some of the puzzles of the game were clever and fun, others felt like busy work when I really wanted to experience more of the tale being told. Condensing the experience would go a long way to connecting the player to the narrative.

To be fair, I’ve played this game after playing Journey. Journey does an exceptional job of keeping the player engaged throughout the entire experience. By contrasting the two you can see how Papo & Yo can be improved. Most of that is because just controlling the character is a unifying experience for the player. There is no moment where you feel disconnected from the character and the story elements are presented throughout the experience.

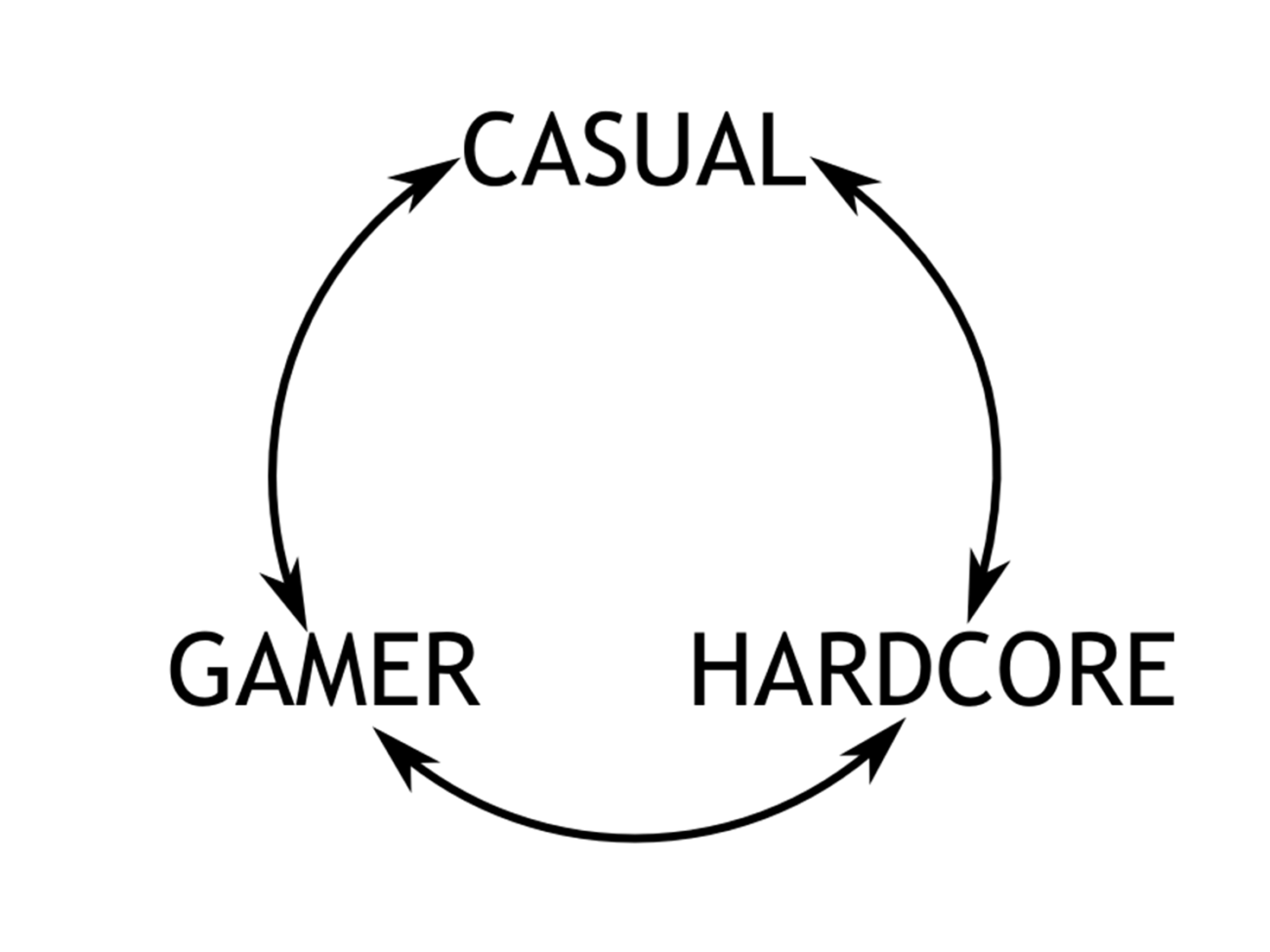

Overall, the game did a good job of presenting a brief and deliberate window into the auteur’s life. It was palatable and not overly preachy. I think it shows one can deal with subject matter other than saving the world from an alien invasion. Such serious topics can be expressed through games and can use different perspectives, such as a young boy, to tell a story. If more developers can take personal tales and express them through interactive entertainment, the game industry will take giant steps toward widening market beyond the typical gamer. Papo & Yo shows the mainstream that not every game has to be some young boy’s escapist power fantasy.

You must be logged in to post a comment.